ON THE SEARCH FOR THE VIOLIN CONCERTO IN E MINOR, WoO 15, BY FELIX DRAESEKE

|

Preface: This article paper was originally written in September-October

2000

and was delivered at California University of Pennsylvania

on 28 October 2000 during the fall meeting of

the Allegheny Chapter of the American Musicological

Society. It has been revised and updated in the new version here in the hope that it will assist in some way in

the recovery of the manuscript of the only known copy of the orchestral score

to Felix Draeseke’s single work for violin and orchestra, his Concerto

in E minor, WoO 15. Anyone wishing to respond to the paper and its purpose of

inquiry should do so by this form or

by

regular mail to: the

International Draeseke Society/North America, Box 104, Sand Lake, NY 12153

or Internationale

Draeseke Gesellschaft, Fürstenbergstraße 9, D-88633 Heiligenberg (Deutschland). An updated version of this article, in German, from 2009 is available. |

||

|

|

From the title of this paper one may correctly assume that it is an account of research in progress, of research which will not end until it has been definitely established if the orchestral score and (presumed) set of parts for the Concerto in E minor for Violin and Orchestra, WoO 15 of Felix Draeseke are still in existence (and where) or whether they have been irretrievably lost. Has the concerto completely disappeared? This question can be answered with a qualified "no", and what follows is a report on the facts relevant to this answer. Felix Draeseke (1835-1913) wrote very little for solo instrument and orchestra. There are, in fact, only four: the Concerto in E flat major for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 36 (1886), the Symphonic Andante (Symphonisches Andante) for Cello and Orchestra, WoO 11 (1876), the Concerto in E minor for Violin and Orchestra, WoO 15 (1881) and a work for solo harp and orchestra, Feenzauber (Fairy Magic), WoO 36 (1910) which, like the violin concerto, has remained unperformed to this day. Only the piano concerto has appeared in print, though a movement of the violin concerto was published in an arrangement for violin and keyboard in 1915 (more about that later). The Symphonic Andante, though performed in 1935 at a concert in Coburg honoring his 100th birthday, was never published, for the work poses a perplexing problem: although the score is complete (and musically magnificent!), its rondo-like outline requires the cellist to either improvise or write out his or her own cadenzas between sections, something about which Draeseke is emphatic in the manuscript orchestral score. The version used in its 1935 premiere is still extant, but the question of the supplemental work required by a cellist remains a hurdle for any considerations of publication. There is minimal correspondence by Draeseke concerning his Violin Concerto in E minor, WoO 15, but that which is preserved in the Draeseke holdings of the Saxon State Library (Sächsische Landes- und Universitätsbibliothek [SLUB]), Dresden reveals that he regarded the concerto highly and held hopes for its success almost to the end of his career. From the composer’s own documentation we know that the composition of the concerto was reasonably fast. The first movement, Allegro appassionata (4/4), was begun in early spring 1881 and was completed on the 1st of May that year. The second movement Adagio (3/4) and third movement Allegro con brio e vivace (3/4) carry the respective completion dates of July 12th and July 14th, or about two and a half months after the first movement. Why the violin concerto never achieved a complete performance during Draeseke’s lifetime seems inexplicable. If the composer seems to have lost some interest in it in the immediately succeeding years, such a state might be explained by the enormous exertions of the Symphonia Tragica (Symphony No. 3 in C major, Op. 40) and the opera Gudrun which followed close on the heels of the violin concerto and were his major preoccupations from 1882 to 1886. Why the violin concerto remains unperformed to date in its complete orchestral guise, can only be related by a series of unfortunate events culminating in the disappearance of the manuscript orchestral score sometime between 1941-45. To be sure, there is an arrangement of the concerto’s second movement Adagio for violin and keyboard published by Ries & Erler which dates to 1915, two years after Draeseke’s death and with evident approval of his widow Frida. This movement is the only section of the concerto which has ever been performed publicly – the first time while Draeseke was alive. Eric Roeder, Draeseke’s first biographer, reports on page 94 in the second volume of his invaluable Felix Draeseke. Der Lebens- und Leidensweg eines deutschen Meisters (Felix Draeseke. The Path of Life and Suffering for a German Master, Berlin, 1937) that in April, 1886 the concertmaster of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Adolf Brodsky, performed the Adagio from manuscript "…bei einer geistlichen Abendmusik" (during an evening of musical meditation). Since there is no record of orchestral parts for the performance and since it took part in the Thomaskirche in Leipzig, one can assume that Brodsky was accompanied on piano or what seems even more likely, on organ. Although there is no record of Draeseke’s attendance, such cannot be excluded. Brodsky seems to have been only one of a handful of violinists who had expressed interest in Draeseke’s concerto at the time and the composer allowed Brodsky to retain the violin and piano reduction of it until October 1888, at which time he requested it to be returned: in a letter from 1881 [SLUB] to one of his aunts, Draeseke actually expressed his hope that August Wilhelmj would give the premiere – "…otherwise there are only Jews" – adding unapologetically later "...I’m a confirmed anti-Semite." Wilhelmj did indeed look at the score, but promises of collaborative revision never materialized and Draeseke's concerto eventually found its way back to its composer. Ironically thereafter, the aforementioned Adolf Brodsky – himself a Jew – appears as the only violinist of Draeseke's day to have actually publicly played any of the work – the Adagio – before Draeseke, in the hope of satisfying a prospective publisher, requested its return.

As mentioned above, the Adagio second movement, arranged for violin and piano by Hans Benda [1] was published with evident blessing by Frida Draeseke in 1915 by Ries & Erler in Berlin, though Erich Roeder is not kind to this Benda edition and describes it as "eine Bearbeitung" (an "arrangement") though the English translation does not convey the pejorative implied by Roeder’s comment, since the German can be rendered as a "reworking" as well and states that it doesn’t agree with the composer’s manuscript. Evidently Frida Draeseke, who could be quite demanding in the management of her husband’s estate, considered it good enough and allowed Benda to publish it. Whether Brodsky contributed to this edition or influenced its publication is not known. Comparison of this printed movement with Draeseke’s own surviving violin and piano reduction [ms SLUB] reveals that only the opening and closing measures remain the same. Hans (Jean) Benda’s "arrangement" is a reworking in terms of a Fritz Kreisler free fantasy and far more virtuosic than anything in Draeseke’s original itself. The only complete analysis of Draeseke’s violin concerto which has ever been published is that by Roeder in his previously cited biographical study of the composer, and its major point of reference is the presently missing orchestral score. For those unacquainted with Roeder’s basic, but often suspect, Draeseke study, one should be aware that one of its must frustrating and problematic aspects is an almost total lack of music examples for the author’s analyses of compositions. As interesting and as apparently filled with insights as they may be, Roeder’s analyses present next to no idea of what themes or passages sound like. Draeseke scholars have been unable to satisfactorily determine whether Roeder, after publishing the two volumes of his study, had intended a supplementary volume containing music examples for his verbal descriptions of them. Considering the large number of Draeseke compositions unpublished, or generally unavailable to the public in 1938 when the final volume began to circulate, one must wonder just what it was that Roeder hoped to achieve in his nearly 600 pages of verbal analyses, other than touching the nerve of instinctive enthusiasm in the "true" German, a basic tenet of his Nazi faith. Roeder can be very cunning and devious in accounting facts, and it is only after initial readings of his text that questions begin to arise concerning motivations, performances, reactions and sequence of events. The beginning of Roeder’s analysis of Draeseke’s violin concerto is a point in such discussion, for his analysis begins not with the first movement, but with the second, the aforementioned Adagio and his opening statement is completely without context: "Gerade dieser zyklisch angelegte 2. Satz (Adagio, 3/4) hätte unsere um ein gutes neues Konzert verlegenen Geiger aufmerksam machen müßen" ("It is precisely this cyclically designed second movement [Adagio, 3/4] which would have to attract the attention of our violinists of today who seek a new and worthwhile concerto"). "Cyclical" usually refers in music to the overall design of a concerted (and usually multi-movement) work, requiring both precedent and antecedent to make any formal sense. In

the remainder of his analysis of the Adagio it slowly becomes

apparent that Roeder is simply referring

to A-B-A outline and repetition of material in the development

of the movement and is not mentioning any of the Adagio’s

themes being related to or recalled in material of the

movements which flank it. Roeder then continues his analysis

with observations

about the concerto’s first movement (Allegro appassionata,

4/4), mentioning that it begins without introduction in

the home key of E minor and the immediate entrance of the

violin with

the main theme contained in its "Triolenmotiv,

Baustoff für das ganze Werk (Einheitsthematik)" ("Motivic

triplet motion, building material for the whole work [thematic

unity]"). Roeder’s descriptive analysis makes

reference to a number of unusual maneuvers on this first

movement, but

without a score, much less some music examples, a verbal

recounting of what Roeder has written obviates his observations.

The same

can be said for his treatment of the finale (Allegro con

brio e vivace, 3/4) a rondo which re-introduces material

from the preceding movements before a final virtuosic dash

to the

end. Roeder “describes” the movement as a saltarello

- Draeseke actually writes the word in his score! – because

of the rhythmic emphases in the main themes and suggests

that it was inspired by a visit of Draeseke to Ischia the

preceding

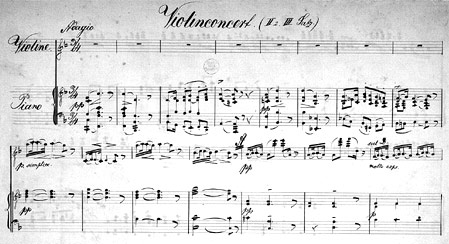

year. Although the orchestral score and presumed set of parts for Draeseke’s violin concerto have disappeared, the work is not really "lost", for a violin and piano reduction, obviously made for rehearsal purposes, is housed in the music manuscript collection of the Saxon State Library in Dresden under the catalog entry MUS 7099-B-501. There are two folios. The first contains movements 2 and 3 (Adagio and Finale) and the second, the first movement (Allegro appassionato). This unusual juxtaposition of folios may account for the catalog entry’s parenthetical note of "unvollständig" (incomplete) and could lead one to the conclusion that there is music missing from this reduction. A pdf version of the SLUB mansuscript is available at draeseke.org. The concerto is 100% intact, though this writer’s microfilm from SLUB did not include a solo violin part, possibly another reason for the term "unvollständig" on the entry. All of the pages of this reduction are in perfect numbered sequence: 27 for the first movement, 6 for the Adagio and 15 for the finale and there are no measures missing or crossed out. When ordering the microfilm for this material, it was verified and guaranteed that the folios were received in exactly the juxtaposition described above, directly from the estate of Frida Draeseke and the catalog entry, in consideration of that, will evidently not be changed. It doesn’t take a particularly well-trained eye to note the discrepancy in the spelling of Violinconcert (with two "c's" instead of the more normal German with a "k" and "z": Violinkonzert) on the folio containing movements 2 and 3, but Violinconzert on folio 2 with the first movement. The handwriting seems different between the two folios, though there is no existing correspondence indicating that Draeseke paid copyists for the violin and piano reduction. Roeder’s discussion of the concerto in his study of Draeseke makes frequent reference to material presented by various instruments and instrumental groups throughout the work, so it is obvious to assume that he was working with the orchestral score which, alas, seems to have been the only copy ever made. Whether this score is lost irretrievably, one cannot say, since the search for it has only been underway for a short while and with admittedly piecemeal endeavor. When did this score disappear? How did the score disappear? In reference to question No. 1 the answer is simply: sometime between 1941 and 1945. There is no answer as to how it disappeared. Speculation reigns at present as to its possible (though not exact) location, and there is the possibility that the orchestra score was lost or destroyed during the Russian sweep through Silesia toward the end of the war: the last place the score was known to be, was Liegnitz (today Legnica in Polish), a town which suffered enormous damage during the Russian advance.

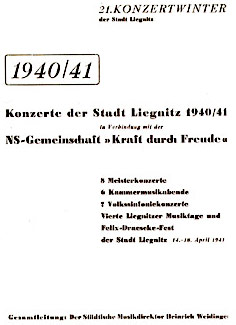

The

1941 program for the week's offerings appears as an appendix

to this paper. Aside from being mailed

from the Liegnitz

concert

If one looks at the first two planned orchestral concerts on the program, one notes that both Draeseke’s violin concerto [5] and symphonic poem Frithjof were receiving their first performances. In the paragraph following the above quoted letter by Heinrich Weidinger in the Mitteilungsblatt, the FDG reports that the composer’s widow, Frida Draeseke, who had died 14 November 1942, had assumed the costs for the preparation of the score and parts for not only Frithjof, but also for the symphonic poem Julius Caesar, the composer’s first effort in the genre. There is absolutely no mention of preparation of a fair copy orchestral score and corresponding set of parts for the violin concerto, despite the fact that the violin concerto was announced for performance – the symphonic poem Julius Caesar was not. The situation with the violin concerto becomes even more intriguing when one reads a page or so later in the Mitteilungsblatt that the wishes expressed in Frida Draeseke’s will and testament regarding her husband’s works are being carried out according to her instructions: namely, that Draeseke’s manuscripts were to be housed in the Dresden State Archives. A certain Dr. Müller-Benidict was in charge of the reception and cataloging of the manuscripts and he sent a list of the received manuscripts to the governance of the Felix Draeseke Gesellschaft, which at the time was in the hands of Erich Roeder and Dr. Hermann Stephani (a pupil of Draeseke’s and author of the entry on Draeseke in the first edition of Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart). No list was found among Stephani’s personal effects after his death in 1960 and any list which Roeder may have had has ever been found and Dr. Müller-Benidict's own list of manuscripts was evidently considered irrelevant or unimportant when the communist regime of the German Democratic Society "reorganized" libraries within its state. However, among the works mentioned in the Mitteilungsblatt Nr. 7 of the Felix Draeseke Gesellschaft received by Müller-Benidict there is no mention of a manuscript of an orchestral score for the Violin Concerto in E minor, WoO 15, nor any reference to a set of performance parts. Only the violin and piano reduction is noted.That is where the mystery remains. The postwar dissolution of the Felix Draeseke Gesellschaft is badly documented. Suffice it to say that by 1962, two years after the death of Hermann Stephani, the one substantial source of funds as well as the source of legal credibility for the Felix Draeseke Gesellschaft, the composer’s home town of Coburg, disassociated itself from the cause of Felix Draeseke and withdrew support of the society. Few people in Coburg at that time had much interest for the composer, a situation exacerbated by perception that his own musical style and his personal associations during his lifetime aided the rise of Nazism. Yet there was a younger generation of musicians, music historians, and members of the musical public who would be awakened to the cause of this remarkable composer and especially after 1980, organize a new society on behalf of his music: the Internationale Draeseke Gesellschaft (1986) and later the International Draeseke Society / North America (1993). This author is, of course, part of that younger generation. As an undergraduate at Syracuse University between 1957-61 this writer had the good fortune to make the acquaintance of a music librarian at the time, Mrs. Antje Lemke, recently arrived from East Germany and, as it turns out, daughter of the eminent theologian Rudolf Bultmann. The display of astonishment which came over her when this writer mentioned the name Draeseke to her in the spring of 1959 gave way to an eagerness to put me in contact with all who she knew to have been personally associated with Draeseke or had been active in the Gesellschaft. Mrs. Lemke translated my first letters of inquiry to Hermann Stephani, then in his final years at the University of Marburg in West Germany. In one of those letters, calling Stephani’s attention to my violin teacher Louis Krasner, the man who commissioned Alban Berg’s violin concerto, it was suggested that Krasner might have interest for Draeseke’s violin concerto. Stephani dealt with this naive inquiry in a cryptic, but friendly, manner: "Das Konzert liegt wohl heute in russischem Bestand" (The concerto is probably today in some Russian collection) [6]. That remains even today the leading clue as to the possible whereabouts of the orchestral score to the Violin Concerto in E minor, WoO 15 by Felix Draeseke. Music examples are reproduced with permission of Saxon State and University Library Dresden (catalogue signature number MUS 7099 - B - 501). The full copy of the score to the Violin Concerto in the piano reduction is available on line. Notes 1. It is mentioned in the body of the paper that the arrangement of the Adagio which was published in 1915 is by Hans Benda. This is the name provided in the IDG Felix Draeseke Chronik seines Lebens, but Erich Roeder ascribes it to a Jean Benda. To be sure, Jean is the equivalent for the German (Jo)hannes. Although initial speculation suggested that the arranger was the noted conductor Hans von Benda, it has now been ascertained that Hans (Jean) Benda is the virtuouso violinist and pedagogue who was active in Berlin in the first part of the 20th Century. See also the update of June 2009. 2. From hearsay the author included the rank of Erich Roeder as that of lieutenant. Others have offered conjecture but not verified facts. The ranks of captain and major have been suggested. Clarification is needed. 3. Whether there was in the Wehrmacht an organization or department specifically named Sonderdienst Kultureinsatz has also not been established, although some unit regarding cultural operations did exist, especially for newly conquered territories. In 1941 Liegnitz was a German city and, as such, such a unit may not have been operative, though the Polish occupation between the wars may have warranted such a unit in the eyes of the Nazis. Clarification is needed. 4. There has been no response for information concerning Heinrich Weidinger, the Liegnitz music director in 1941. Information regarding him would be welcome. 5. There has been no response for information regarding the post-1941 career of the proposed soloist for the premiere of the Draeseke violin concerto, Willibald Roth, then concertmaster of the Dresden Staatskapelle . Attempts to contact direct descendants have been thus far to no avail. In formation regarding Willibald Roth would be welcome. 6. The letter from Hermann Stephani to this author from 1959 which simply states that Draeseke’s violin concerto is probably in a Russian collection, was surrendered to Martin Stephani, along with several others written to this writer by his father, when the author visited Martin Stephani at his office as director of the Detmold music conservatory in September of 1961. One assumes that the letters are part of the late Martin Stephani’s estate. 7. The first complete performance of Draeseke's Violin Concerto (piano and violin) as well as a performance of the Benda arrangement of the Adagio, took place at the June 2009 IDG Conference in Meiningen and Bad Rodach (click for details). © Alan H. Krueck 2000/2009 |

|

Related web pages:

|

||

[Chamber Music] [Orchestral Music] [Keyboard Music] [Listen: mp3 - Real Audio] [Top]

© All contents copyright by the International Draeseke Society

The

place chosen for the festival was the Silesian city of

The

place chosen for the festival was the Silesian city of

association, this program was also printed in the Mitteilungsblatt Nr.

6 of the Felix Draeseke Gesellschaft issued in early 1941.

An explanation for the ultimate postponement

of this festival had to wait for the society’s Mitteilungsblatt Nr.

7 which the FDG issued in the late spring of 1943 -as it

turned out, this would be the last official Information

Sheet

from the Felix

Draeseke Gesellschaft ever. The booklet is barely twenty

pages long, but it is crammed with invaluable

information

relevant to Draeseke research and above all, in reference

to Draeseke's’s violin concerto. On what is the 8th

numbered page the editor of the document reproduces a letter

received

from the civic music director in Liegnitz and official organizer

of the Draeseke festival, Heinrich Weidinger

association, this program was also printed in the Mitteilungsblatt Nr.

6 of the Felix Draeseke Gesellschaft issued in early 1941.

An explanation for the ultimate postponement

of this festival had to wait for the society’s Mitteilungsblatt Nr.

7 which the FDG issued in the late spring of 1943 -as it

turned out, this would be the last official Information

Sheet

from the Felix

Draeseke Gesellschaft ever. The booklet is barely twenty

pages long, but it is crammed with invaluable

information

relevant to Draeseke research and above all, in reference

to Draeseke's’s violin concerto. On what is the 8th

numbered page the editor of the document reproduces a letter

received

from the civic music director in Liegnitz and official organizer

of the Draeseke festival, Heinrich Weidinger